A warm welcome to the Deeper newsletter, dear reader!

You’re reading this because, just like us, you’re tired of the non-stop tech and startup news cycle, where there seems to be something new and trendy to keep up with in Southeast Asia.

What you want to know about is the important stuff that matters—period.

And that’s what we’re bringing to you. We’ll dive deep into a trending topic in Southeast Asian tech, and their impact on society (i.e. me and you).

Sound compelling? Subscribe now, and we’ll send it straight to your inbox:

Without further ado, let’s dive in.

Many observers believed that 2020 would be a stellar year of healthy growth for delivery platforms.

Over the first half of 2019, GrabFood recorded threefold growth in gross merchandise value (GMV) in Indonesia, and had plans to expand to 19 new cities and townships across Malaysia in 2020. Indonesia’s GoJek reported collaborations with 400,000 GoFood partners—96% of whom are micro, small, and medium enterprises—and the firm stated in October that they were finally going to “stop burning money”.

That was before COVID-19.

This months-long pandemic has placed an inordinate strain on food delivery platforms, which now carry a major responsibility to feed hungry populations in ASEAN as lockdowns and quarantines limit physical movement. Globally, the online food delivery market is worth more than US$35 billion annually and is forecasted to reach US$365 billion by 2030. This space is diverse—delivery “pure-plays” like Deliveroo and FoodPanda compete with super apps like Go-Jek and Grab—with plenty of room for new competitors to edge their way in.

Food delivery platforms have been criticized in the news and by buyers and restaurants who believe their commissions are too high, their incentives too low, and their practices too greedy. The mounting pressure to be more socially responsible and less profit-motivated will threaten the possibilities for IPOs within the next 3-4 years.

TL;DR: The food delivery industry in ASEAN is shaping up to become even more competitive and tricky, with many more challenges for incumbents ahead:

- The state of food delivery in ASEAN

- Increased demand isn’t leading to healthy profits or growth

- Delivery platforms find themselves in a high-pressure cooker situation

- More major obstacles to profitability are looming ahead

- Cutting out the middlemen

- Communities are coming together

- Institutional actors are also playing a part

- The way out of a sticky situation

In order to become profitable, on-demand food delivery startups must become much more efficient and navigate a tense social landscape while proving that their practices are fair and supportive.

The state of food delivery in ASEAN

Different local giants dominate different countries in ASEAN. FoodPanda, which is headquartered in Germany, has major presence in the ASEAN countries of Malaysia, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Singapore. Reportedly, even its slowest growing markets have seen growth of over 300%—and in some cases, the company has seen up to 20 times growth within 12 months.

In Indonesia, consumers have two choices: GoFood (GoJek) or GrabFood. And GrabFood onboarded more than 1,500 merchants in Singapore since January, though not all seem to be happy.

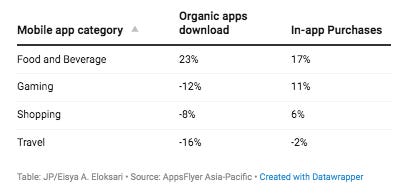

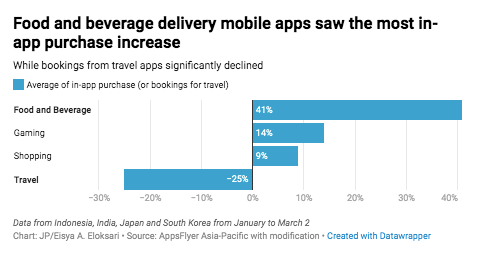

A study by American based mobile marketing analytics and attribution platform AppsFlyer showed that downloads of food and beverage (F&B) delivery applications rose 23% from January to early March in Indonesia. Meanwhile, transactions from said applications rose 17% over the same period.

The survey also showed that in-app-purchases within F&B delivery apps increased by 41% on average in Indonesia, India, Japan, and South Korea. Many other countries, including Great Britain and Kenya, mirror this increase in food delivery app usage.

In Vietnam, e-commerce delivery startup Loship saw a record 80% surge in the number of food orders on its app in mid-March. Over 1,000 new eateries signed up for the service in April, far exceeding its previous monthly record.

FoodPanda, GoFood, Loship, and GrabFood operate through the same business model—by collecting orders from buyers, relaying them to establishments, and operating a fleet of drivers to deliver the meals. Most delivery platforms around the world collect anywhere from 15 to 30 percent of restaurants’ revenue.

Prices for food delivery vary widely across ASEAN—online food delivery in Singapore can be five to 10 times higher compared to markets in Indonesia and Vietnam, where couriers may deliver food for as low as $2. These regional disparities mean that companies must create highly localized commission systems in order to maximize their own cut while still paying a fair fee to drivers.

But increased demand isn’t necessarily leading to healthy profits or growth

Unfortunately, the increased demand in food delivery hasn’t actually translated to profit for the delivery intermediaries or the restaurants providing the grub. In response to viral posts and pushback from restaurant owners and communities, Grab Singapore released an announcement insisting that despite increased demand, they were neither profiteering nor profiting.

Delivery platforms are in a high-pressure cooker situation

Food delivery platforms on the whole aren’t faring so well. The wave of scrutiny and suspicions of profiteering following the many viral posts and protests from restaurant associations means they won’t be able to raise commissions without public uproar. In April, the Restaurant Association of Singapore (RAS) called for food delivery players to lower their commission rates, emphasizing that current commission fees were very high given F&B’s razor-thin margins.

Now that food delivery has become an essential service in virtually every country, more and more competitors are emerging to fight what many feel are unfairly high costs.

Food delivery platforms aren’t entirely to blame for this situation. Food delivery as a channel was never supposed to replace dine-in sales, so asking platforms to reduce restaurant commissions or provide more significant assistance to struggling establishments isn’t entirely fair. The platforms are just as in need of help as the restaurants they serve.

So far, Singapore is the only ASEAN country where government organizations are providing help to cover food delivery costs. Enterprise Singapore has agreed to fund five percentage points of the commission cost of GrabFood, Deliveroo, and FoodPanda. This may not be enough to help, however. F&B establishments are seeing as much as a 70% drop in revenue in Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, and other countries in the region.

Major obstacles to profitability are looming ahead

When COVID-19 arrived, most of the big food delivery platforms were engaged in a war of discounts—paid for with investor money. The huge promotions (up to 50% or 60% off meals) and generous driver incentives were a tactic many used to gain critical mass, and the pandemic arrived before platforms had time to wean users off the promotions.

Fears of profiteering, though not unfounded, fail to address the reality of the situation—which is that food delivery platforms aren’t thriving at all. Deliveroo is laying off a quarter of its 80-strong Singapore workforce as part of a global cut that will hit over 300 workers. And in a recent update to its Australian partners, it apologized for its inability to provide commission relief as the outbreak has been “challenging for all businesses and we’re providing assistance where we can.”

At the beginning of the month, Grab Singapore’s head of transport Andrew Chan said: “As our revenues continue to fall, senior Grab leaders have taken a pay cut of up to 20 per cent and Grab staff have also been encouraged to take no-pay leave voluntarily.” Additionally, a weekly payout of $45 or $85 to help supplement drivers’ income was extended to end-May.

The funds for this assistance are sourced from the pay cuts, as well as cuts to incentives for best-performing drivers and cancellation compensation. Grab employees also made voluntary donations, matched by the firm to fund the extension of financial assistance.

Every company is doing its best, but it’s a dog-eat-dog world out there, and restaurants and hungry customers can’t afford to have too much empathy—they also need to survive. As a result, they’re seeking their own solutions to deliver food to hungry customers.

Cutting out the middlemen

Many establishments are now encouraging buyers to contact them directly to order. Cutting the intermediary out reduces the amount spent on commission, and customers can enjoy cheaper menu prices.

Food delivery platforms are marketplaces. Too often, their marketing campaigns prioritize restaurants that offer discounts upon discounts (there are 56 active promotions in my GrabFood right now).

Larger chains may be able to handle these marketing costs, but small- and medium-sized F&B establishments that have just opened or are still building a client base are already operating on razor-thin margins. Huge fees on top of significant discounts make it impossible for them to pull in revenue.

Mr Anthony Yeoh, who owns Summer Hill bistro, posted on Facebook last month that he decided to turn off the GrabFood terminal for his bistro food delivery and would use couriers instead. He explained that the fees were too large for him to stomach.

Communities are coming together

Food delivery isn’t always for-profit. Villages and urban communities in Thailand have banded together to help their neighbors by launching dozens of local food banks across the country. These “Pantry of Sharing” locations have sprung up in 44 provinces across Thailand and number more than 150 cabinets.

Another initiative in Bangkok is Locall, created by the same founders of the crowdsourcing map STRN Citizen Lab (another initiative prompted by COVID-19). The Locall community helps diners order from popular street food stalls in Bangkok, Pratupee, Nanglingee and Yaowarat by receiving messages via a LINE Business account, purchasing food on buyers’ behalf, and delivering the meals. The minimum spend is B300 and delivery fees start at B30.

Customers empathizing with smaller F&B establishments have collated resources to help spread the word about their offerings. In Singapore, these directories include the Kudos SG Facebook group, the Singapore Food Promotion and Delivery Facebook group, Dabao.life, WhereGotFood.sg, the Hawkers United – Dabao 2020 Facebook group, and Manyplaces.sg.

Local communities are feeling a need now to band together and support their fellow diners and F&B restaurants. But the question is whether they’ll persist even after COVID-19 has passed and establishments are no longer totally dependent on food delivery for income.

Institutional actors are also playing a part

Singaporean property developer GuocoLand started a non-profit initiative called #GTFoodDelivery in April to support tenants in Guoco Tower (formerly known as Tanjong Pagar Centre). Buyers can order from up to three F&B establishments and enjoy free islandwide delivery if they spend over $50 (the minimum spend to place an order is $30).

Orders that don’t hit the $50 threshold incur a flat delivery fee of $5. “All sales go straight to our merchants,” writes GuocoLand on the site, “and delivery costs are fully subsidised, letting merchants retain most of their margins.”

New competitors are emerging

We’re also seeing older companies from adjacent verticals pivoting to the delivery space. Hong Kong’s “A Guide to the Best Meal” initiative is a cross-district food delivery service hosted by on-demand parcel delivery startup Lalamove and travel activities booking platform Klook. Customers can order from a selection of favorite dishes on Klook’s website or mobile app, then arrange a delivery time with Lalamove.

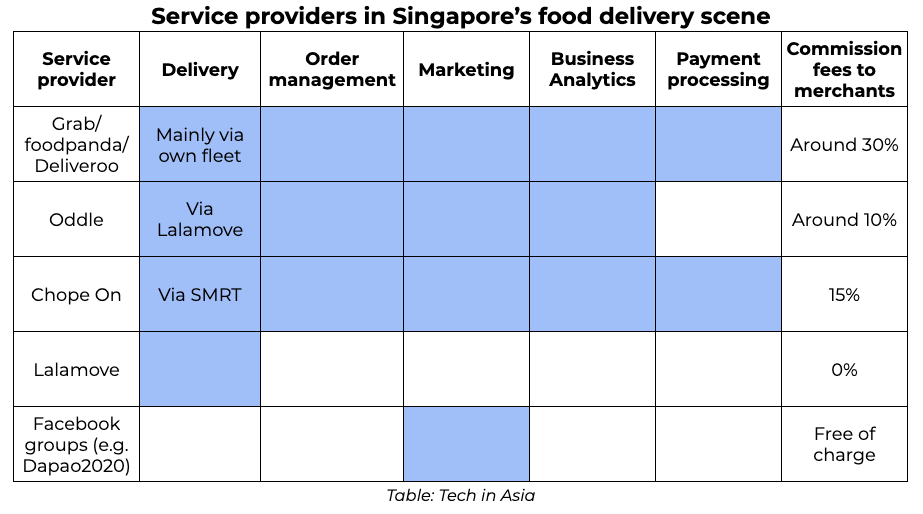

Singapore is an especially busy scene

Lalamove’s managing director Alex Lin says that the demand for F&B-related deliveries has grown 300% since the start of April. He expects this to increase by a further six to seven times in the coming weeks. Restaurant booking app Chope launched its own delivery service in the nation-state together with local taxi operator SMRT after just three days of development—commissions are capped at 15%. The service is still in beta phase and is able to offer lower commissions because the restaurants it serves are middle to high-end—meaning that order amounts are higher.

Another interesting competitor is Oddle, which functions as a white-label online ordering platform. In Oddle’s unique pay-on performance model, the company only takes a 10% cut of actual online sales—meaning that they must ensure that their partners do well. To date, it is used by nearly 3,000 premium F&B brands spread across Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Co-founders Jonathan Lim and Alan Goh shared, “Oddle was initially launched for the sole purpose of providing a technological solution for restaurants to have their own platform to capture organic sales. As time went by, we realised they don’t have the logistics manpower support. So we found delivery partners in different markets to handle that part of the operations.”

The way out of a sticky situation

On-demand delivery startups are trying a number of tactics to lower costs and reach profitability while combating the aforementioned challenges.

Cloud kitchens

Cloud kitchens began gaining traction in Q3 2019. These shared kitchen spaces are like coworking spaces for restaurants, which can lease space in a more centralized location to fulfill delivery app orders. Grab said it currently has 10 cloud kitchens in Indonesia, with plans to build more in the country and across the region by the end of the year.

According to Grab, cloud kitchens:

- unites multiple F&B brands in a single central facility

- to solve the cuisine gaps in specific areas

- by leveraging data to identify and map gaps in consumer demand

With GrabKitchen, merchant partners are able to grow their business in a low-cost and low-risk way by expanding into new areas beyond their original locations. This also allows them to tap into a new consumer base via GrabFood, through which merchant partners enjoy greater visibility.” FoodPanda and GoJek are also creating their own cloud kitchens.

Cloud kitchens can be helpful for small restaurants, but beware of placing too much power—and becoming too dependent on—the kitchen operator. One industry insider warned that, left unchecked, food delivery platforms may actually take data from the most popular restaurants on their platform and eventually release their own optimized versions of the same menu—becoming competitors of the establishments they’re supposed to serve.

One example of a successful full-stack cloud kitchen is Singaporean startup Grain. Founded in 2014, the startup focuses on healthy meals and business catering delivery, with zero dine-in options or physical locations—and they full ownership over every aspect of their business, including production and delivery. Grain successfully raised a $10 million Series B round last year and has been profitable since then.

New order formats

GrabFood Singapore has begun trialling a pilot project to win over hawkers with lower commission fees. The “Hawker Centre 2.0” pilot initiative, which began on May 11, is being implemented at AMK 724 Food Centre, with 12 stalls already in the program. Hawker Centre 2.0 seeks to apply digitalisation concepts to hawker stalls and collect data on how to improve hawkers’ selling journey, while also making order deliveries more efficient by allowing drivers to deliver multiple orders in one trip.

Similar to the cloud kitchen concept, consumers can order from a range of stalls in the hawker centre within a single transaction. Currently, orders from different restaurants or stalls have to be made in separate transactions.

Following Meituan’s footsteps

Chinese super app Meituan is one of the few food delivery platforms that has actually experienced periods of profitability. The company posted an adjusted profit of 4.7 billion yuan (US$660 million) in 2019 after adjusted losses of 8.3 billion yuan ($1.16 billion) the year prior. Uber, on the other hand, posted US$8.5 billion in losses for fiscal year 2019.

Unlike GoFood and GrabFood, which are still tweaking operations in efforts to break even, Meituan Waimai earned US$838 million in profits exclusively from April to September 2019. It’s now active in over 2,500 cities across China with an average of 700,000 active delivery riders each day.

(According to a March 2020 Bernstein Research report, Meituan will see overall operating losses for the first quarter of 2020 because of supply disruptions and safety concerns. Though food delivery revenue is expected to fall by 13%, both analysts and Meituan chiefs expect a “swift recovery” after COVID-19).

Meituan stands out for succeeding despite having relatively low merchant commission fees of 13%. Other platforms continue to operate at a loss despite significantly higher commission fees, causing many competitors to scratch their heads. “Meituan’s key advantage is its low delivery expense, indicating that it has the most cost-efficient delivery system,” Bernstein analysts wrote. Their report cites Meituan’s scale, the high urban density of its market, and low labor costs in China as significant factors.

Other analysts say that Meituan’s success comes from ”relentless attention to operational efficiency.” By obsessing over everything from e-scooter maintenance to incentives structure to order algorithms, the company was able to make an operationally-intensive food delivery model work.

Delivery subscriptions

One last tactic worth mentioning in the battle for profitability is the attempt at food delivery and ride subscriptions. GoJek and Grab both attempted to offer bundle packages to mixed results.

GrabFood Plus was released in January 2020, allowing users to receive discounts on all food orders within the period of subscription, but the service—which offered 50 free GrabFood deliveries for a flat $9.99 fee—was quietly discontinued in April.

A GoFood Pickup feature allows customers to order meals through the app and schedule pickup for later. Premium-priced GoFood Turbo, on the other hand, guarantees food deliveries under 30 minutes.

Thinking lighter and smarter

Grab and Gojek are following Meituan’s footsteps in building ecosystems of products and services, all linked through a digital payments solution. The super apps are hoping to push for cross-sells and up-sells to other verticals, such as travel bookings and orders for gaming vouchers.

Other platforms like UberEats are considering mergers, inciting fear that resulting giants would control too much market share. Governments are being called to keep a close eye should the need for trust-busting arise.

For now, whether or not food delivery platforms will be able to replicate Meituan’s profitability seems to depend on how efficient they can make their driver fleets and order delegation algorithms, as well as whether or not they can keep buyers, drivers, and F&B establishments loyal. This goes for all food platforms—from Deliveroo to FoodPanda to GoFood to GrabFood to those abroad, such as UberEats.

One final factor that may affect the trajectory of food delivery startups is government interference in commissions. Should local governments feel compelled to cap commissions at 15% (like many have requested), platforms will have to scramble even faster to make ends meet. This has already happened in Los Angeles, which implemented a 15% commission cap on GrubHub, UberEats, and similar platforms—and it may happen in Singapore, where the outcry has been the loudest across the region.

Mobile penetration will continue to rise in ASEAN, and the market for food delivery is only going to continue to grow. With any luck, by the time the promotions and discounts are lifted, these platforms will see enough organic revenue growth to cover the drop in income. It’s a long journey ahead, but we’re eager to see which Southeast Asian food delivery startup makes it first.

<

p style=”text-align: center;”>P.S. Like what you read? Get articles like this in your inbox.