A warm welcome to the Deeper newsletter, dear reader!

You’re reading this because, just like us, you’re tired of the non-stop tech and startup news cycle, where there seems to be something new and trendy to keep up with in Southeast Asia.

What you want to know about is the important stuff that matters—period.

And that’s what we’re bringing to you. We’ll dive deep into a trending topic in Southeast Asian tech, and their impact on society (i.e. me and you).

Sound compelling? Subscribe now, and we’ll send it straight to your inbox:

Without further ado, let’s dive in.

We often talk about the importance of digital literacy in bringing ASEAN countries forward, but much of the discourse has been focused on hip younger generations—primary school students, the new workforce, and fresh graduates in metropolitan areas. What about the other players in the region? Surely we can’t leave the tech giants out of the discussion—not when they’ve been such efficient vectors for hoaxes and false news.

And what about the governments that have repeatedly encroached on the public’s right to gain knowledge, ask questions, and share criticism? Thanks to the tech giants’ laissez-faire attitude towards the content shared on their platforms, governments have justified increasingly greedy grabs for individual consumer data and Internet use.

TL;DR: Left unchecked, ASEAN governments will continue to use catastrophes and unrest to encroach on individual freedoms.

- Tech giants and social media platforms need to be more committed to stopping hoaxes

- Governments must stop conflating fair criticism with “fake news”, slander/libel, and hoaxes

- Creating change through a multi-pronged approach that involves multiple stakeholders

To stop this change from happening—or prevent it from fully taking place—tech companies must acknowledge and take responsibility for the critical role they play in spreading information, and the power to voice opinions must be returned to the people.

Social media platforms need to be more committed to stopping hoaxes

Content-based platforms have been allowed to play in their sandboxes for much too long. They benefit from the viral content that users produce and taking money for paid ads without considering the veracity of the information being amplified.

Plenty of people argue that it’s not fair to demand social media platforms do the work of censoring: after all, they’re just facilitating a democratic platform where everyone can speak, right? The onus should fall on readers and consumers to be more careful about the content they consume.

The issue with this type of thinking is that these platforms have too much potential to do damage in the hands of people with funds.

- By unscrupulously accepting payment from any organization with enough money to share their points of view, platforms like Facebook, Google, and Twitter are actually contributing to heavily-skewed (and potentially false) narratives.

- Never mind the fact that scammers also boost posts to monetarily scam people, too.

- Content verification engines aren’t properly flagging spammy or possibly-inauthentic content, essentially allowing hoaxes to proliferate by giving them time to gain critical mass.

- Because these platforms have not fulfilled their responsibility in managing fake content, governments have been able to justify censorship laws to regulate anything and everything they deem “fake news”.

If you think about it, many content-based social media platforms function as User-Generated Content (UGC) publishing companies—ones with far more power than newspapers in days of yore. This means they have a responsibility to filter the type of content that gains traction on their platform—not necessarily by taking a specific political stance, but by carefully discerning whether the paid content is truthful and taking a stand when it isn’t.

Ideally, platforms would take more responsibility to expose inauthentic content as it is created—before it has a chance to spread to messaging platforms like Whatsapp and Telegram.

A recommendation from the Yusof Ishak Institute says, “Global tech giants like Facebook and Google need to increase their public take-downs of content by fake news syndicates and reduce financial incentives for actors to produce disinformation.”

And Nathalie Maréchal, a researcher at Ranking Digital Rights, says, “For something this blatant—and related to what Facebook is saying is currently its top priority—[post-publication removal] is not acceptable. They should be aiming for a 99.99% hoax detection rate before the post ever goes up.”

The fact is tech giants nowadays are arguably more powerful than governments—their reach spans the entire world. They need to be responsible with their function as governors of flow of information about critical issues, and be more transparent about their processes.

Governments must stop conflating fair criticism with “fake news”, slander/libel, and hoaxes

Tech companies’ lackadaisical attitude towards the content they host has allowed governments to justify major civil rights violations against individuals. The issue with codifying punishments for fake news and hoaxes is that, too often, the definition of fake news is manipulated by interested parties who simply want to protect their own reputation.

James Gomez, board chair with the nonprofit human rights group Asia Centre in Bangkok, says that ASEAN government officials are trying to shut down social media activity that harms their reputation—even when the criticism is valid or fair.

Journalist freedom in ASEAN is completely terrible. In the Reporters Without Borders’ 2020 World Press Freedom Index of 180 countries (1 being the most free, 180 being the least) not a single ASEAN country is ranked within the top 100. No matter which country you visit in the region, you’re bound to come face-to-face with vague, draconian rules or regulations that have been used to attack journalists and common people.

Indonesia

In 2017, popular Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) was imprisoned for nearly two years after being found guilty of violating Article 156a of the Criminal Code (KUHP), which criminalizes “blasphemy”.

Activists Dandhy Laksono and Ananda Badudu (former singer of popular indie band Banda Neira) were interrogated by police in September 2019 for criticizing certain aspects of incumbent president Joko Widodo’s policies and handling of specific civil rights issues.

And last week we mentioned how Indonesian comedian Bintang Emon became the target of a Twitter smear campaign from paid Twitter trolls after he jokingly criticized the unreasonably short sentence against two perpetrators of an acid attack that left the victim blind.

Vietnam

A Vietnamese law that took effect on January 1, 2019 made it mandatory for foreign and domestic internet services to hand over user data so that government authorities could probe the address and identity of anyone who wrote “suspicious” content.

Malaysia

Activisists, reporters, and other citizens who have criticized how the government has dealt with COVID-19—the country has the highest number of COVID-19-related arrests in the entire region—have been intimidated and arrested. In the wake of COVID-19, the Malaysian government has also been accused of promoting fear and xenophobia against Rohingya refugees (which are not recognized as such and are instead termed illegal migrants).

Last year, human rights activists Sevan Doraisamy and Rama Ramanathan were taken in for questioning after criticizing Malaysian authorities on social media and through their writing. The police filed defamation charges against Doraisamy under Section 500 of the Penal Code and Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act. Most investigations against activists and government critics have been based on these two aspects of the law.

Philippines

Even before the pandemic began, the Philippines has come under fire for the way it has treated government critics, protesters, and activists. Thousands of activists have disappeared in the country over the years, and a phenomenon called “red tagging”—where activists are falsely branded or accused of being communist insurgents—has also led to numerous disappearances and arrests.

Since the COVID-19 lockdown began, environmental defenders have been punished—one activist was gunned down by unknown assailants in Iloilo City—and over 120,000 people have been arrested for supposedly violating quarantine guidelines such as attending mass gatherings.

Peter Murphy, chair of the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines (ICHRP) says, “Filipino organizations who have been extending relief to those affected by the lockdown are being targeted, arrested and red-tagged by authorities”.

Thailand

Thai social media users have been harassed and intimidated for criticizing the current government and monarchy. On 1 November 2019, one activist was arrested and interrogated by 10 police officers for some viral Tweets criticizing the monarchy.

This was made possible due to the Computer Crimes Act, which was expanded in 2016 to give authorities the license to monitor and suppress online content, and prosecute individuals for a wide variety of reasons, as well as Articles 326 to 333 of the Thai Criminal Code, which criminalize defamation.

Cambodia

Cambodian authorities—like those in many other ASEAN countries—have used COVID-19 as a pretext to arbitrarily arrest government detractors. At least 30 people suspected of being opposition supporters and government critics by claiming that they have spread “fake news”.

And while people are panicking thanks to COVID-19, the government is pushing through a state of emergency law that allows the government to further repress the rights to freedom of expression, association, and assembly.

Singapore

In Singapore, journalists can be jailed for libel, threatening national security, or promoting “ill will” against religious or racial groups—incredibly vague and easy to take advantage of. Singapore is ranked 158 out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ 2020 World Press Freedom Index.

The sweeping Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) was passed in October 2019 and allows government ministers to issue correction notices or even demand removal to media outlets. Earlier in 2020, Singaporean authorities also accused The States Times Review of spreading falsehoods (including about COVID-19).

Creating change through a multi-pronged approach that involves multiple stakeholders

There are a number of steps we need to take to combat hoaxes while protecting individual rights to freedoms of speech.

Tech giants need to be more responsible with their role as content distributors

The issue with allowing Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms to remain as they are is this: they essentially become puppets in the hands of whomever has the most money to pay them advertising bucks.

Rather than supporting the people and helping individuals become more aware of the issues and topics that people care about, they are increasingly acting as loudspeakers for actors with the deepest pockets and biggest bot armies.

I captured five days of tweets using #WestPapua & #FreeWestPapua tags after a crackdown by Indonesian forces against Papuans in Aug. What I found was a bot network spreading pro-govt propaganda.

Follow this thread for an #OSINT journey with a @Twitter network analysis

👇👇👇 pic.twitter.com/N7PrJ33WtJ— Benjamin Strick (@BenDoBrown) September 3, 2019

Tech giants and media companies who don’t tread carefully will continue to be vectors for governmental abusers and online trolls; it is critical that they halt the spread and creation of inauthentic, spammy content on their own platforms. Continuing to blindly accept payment so that people with means (money and bot armies) can manipulate facts to discredit certain groups or movements is what ultimately creates even further civil unrest.

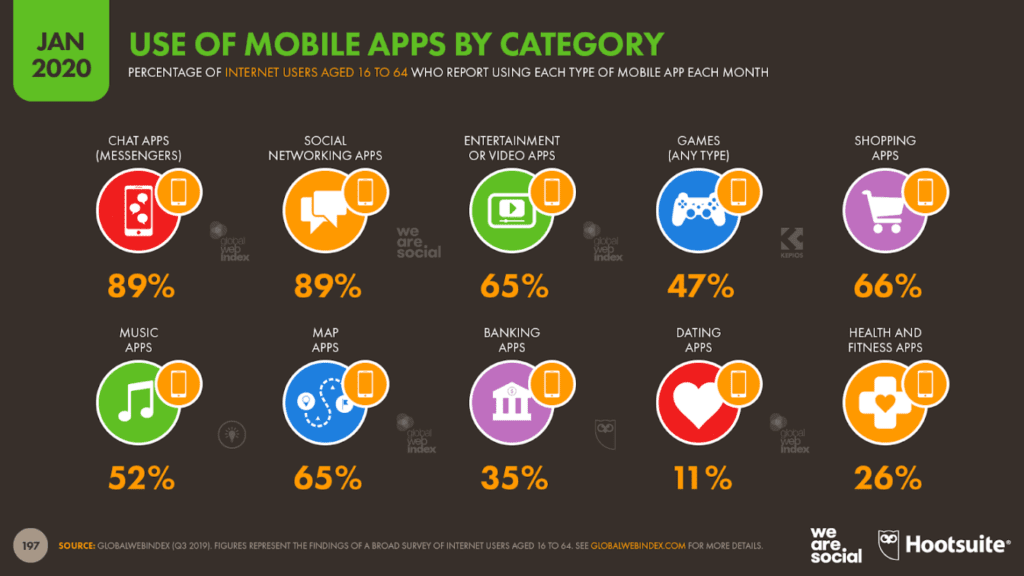

Whatsapp’s unique role in hoax-spreading highlights the need for better digital literacy education

Private social networks such as WhatsApp are a little harder to police. Trigger-happy grannies and grandpas love to use the forward feature to share broadcasts; in my own family WhatsApp group, I’ll often receive over 20 messages a day claiming that some scientist in Egypt or China has discovered the cure to COVID-19.

This may sound funny, but WhatsApp misinformation has also caused more insidious harm. In 2018, two young Indian men were pulled out of their car and beaten to death by a mob after stopping to ask for directions late at night.

“The villagers got suspicious of the strangers as for the last three or four days messages were going around on WhatsApp, as well as through word of mouth, about child lifters roaming the area,” Mukesh Agrawal, a local police officer said. 45 other murders in India were linked to mass paranoia caused by WhatsApp forwards.

WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption makes it difficult to halt the spread of content because no one can see what is being forwarded and sent. Ideally, the platform should continue to commit to punish bulk or automated messaging ( both of which have been violations of the app’s Terms of Service since 2019), introduce fact- and broadcast-verification tools, and educate users on how to spot fake news and hoaxes.

Most recently, the company announced a new forward limit where, if a user receives a frequently forwarded message (defined as one which has been forwarded more than five times), they can only forward it to one chat at a time. Introducing friction into the resharing process could help slow the spread of such falsehoods (the viral hoax that coronavirus is related to 5G led to the vandalization of more than 20 phone masts in the UK).

In the past, users had been able to forward a message to 250 groups at once. This was reduced to 20 a year in 2018, five in 2019, and one now, in 2020. WhatsApp says those measures reduced message forwarding by 25% globally.

Since the main players on platforms like WhatsApp are the users themselves, we do need to do much more work in educating the common person. Media literacy programs need to be targeted to people of all ages—not just the youngest generations who have just recently begun using smartphones and social media. One Indonesian study, for example, found that the vast majority of digital literacy programs are only hosted at university levels—alarming considering a vast majority of citizens have never attended a university class.

Digital literacy programs should be developed holistically by educators and media actors such as newspapers and social media platforms, and implemented with cooperation and collaboration from fact-checking organizations and governments. These don’t necessarily have to be paid courses or school classes.

In fact, we’d also argue that digital media and literacy programs should be disseminated in the same way hoaxes have: through simple, free, and easy-to-digest posts and broadcasts on social media platforms like Twitter, WhatsApp, and Facebook. Take a look at how The Asian Parent has shared tips and information through its Instagram account:

In too many cases, founders and well-intentioned movers create over-complicated solutions to simple problems, and in doing so, fail to actually help the people they’re trying to reach. Why not simply “dumb down” our approach and beat the hoax writers at their own game?

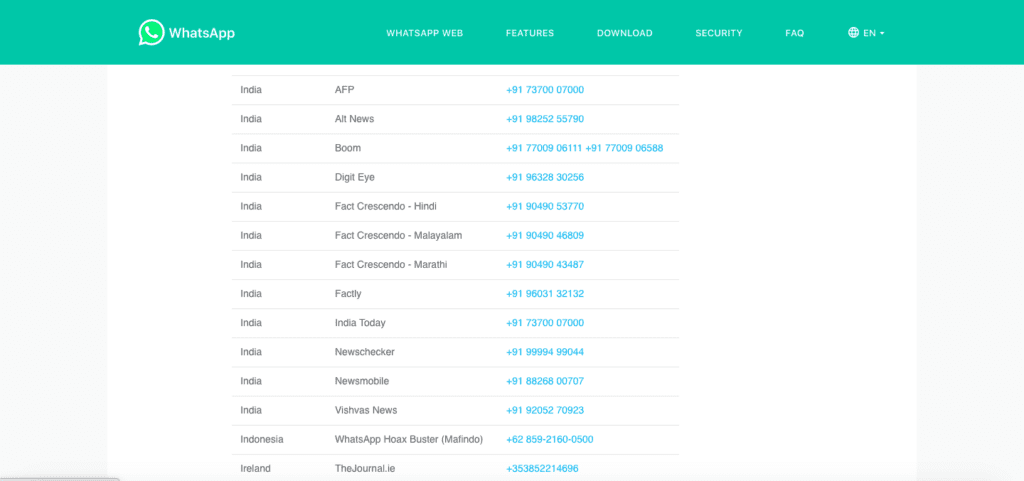

Lastly, aside from increasing friction in the resharing process, tech giants—and WhatsApp especially—need to partner with fact-checking organizations and help users access the verification tools they need.

Put more pressure on governments to stop abusing such vague laws

Seeing the wide range of human and civil rights abuses across Southeast Asia, it remains critical to put pressure on governments and halt the enactment of further laws designed to “protect the public peace” (which really only provide avenues for governments to prosecute naysayers).

This pressure can’t just come from inside a country’s borders. It also needs to come from involved citizens, journalists, activists, and governments of other countries, who could ideally step in to point out rights abuses from a specific government to its own people. Much of this is about taking the initiative to be an informed citizen, and agreeing to hold one another accountable in a shared business and social ecosystem.

In the face of serious health threats like COVID-19, it’s natural to expect governments to take action and restrict some rights, but these should be properly-designed to achieve a specific objective, and only active in times of a clear crisis. (South Korea has done well in this; authorities are allowed to access phone and location information in limited amounts to try and trace down possible carriers of the disease based on where they have been recently, and only during the pandemic).

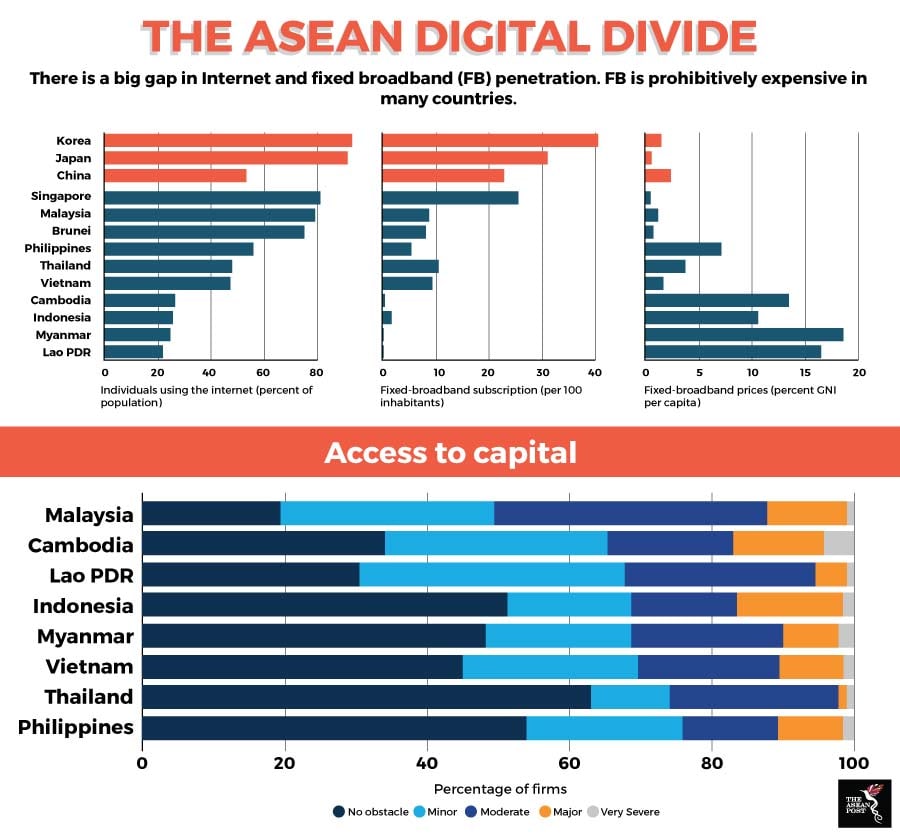

Improve and increase Internet access instead of trying to limit it

Millions of Southeast Asians are coming online in the next few years, but many of them only access Facebook (Lite), Google, and WhatsApp. They mainly communicate with friends and close family members, and may not yet be aware of the enormous potential the Internet has.

This limited digital awareness means that they certainly won’t be verifying controversial content or trying to reverse-image-search to see whether the content they’re sharing is actually truthful. It’s important to widen Internet access and support rural communities in navigating the digital world responsibly and safely.

Create more spaces and increase support for transparent, objective, and fact-based media

Finally, the region needs to nurture online spaces where people can gather, communicate, and verify the creation of online content. We see a lot of activism among global youth, and a lot of righteous truth to power. We shouldn’t be punishing this generational push for more accountability from governments and businesses—digital media, when used correctly, can become a force for positive change.

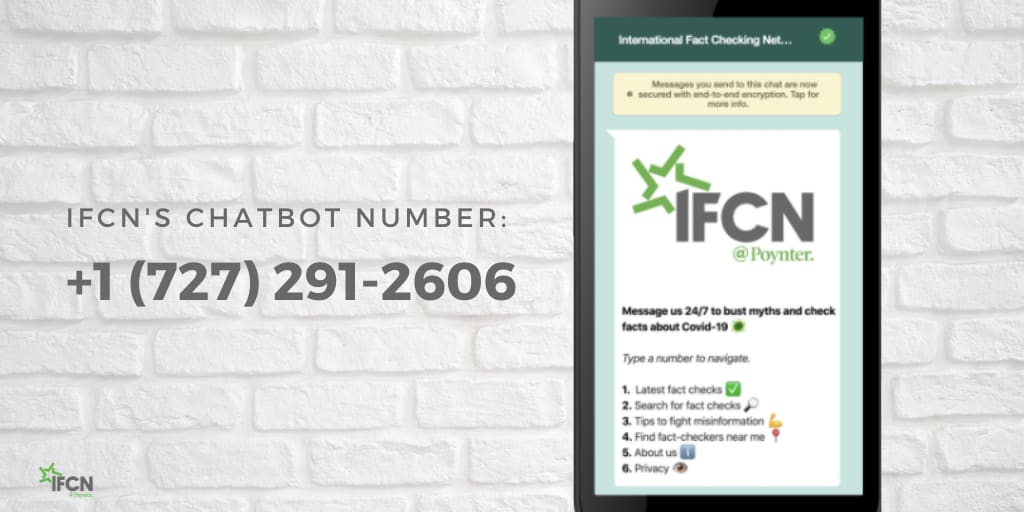

One prime example of a fact-checking organization to support is the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, which hosts the International Fact-Checking Network and also trains fact-checking initiatives around the world. Ideally, these media platforms, channels, and groups would be able to work directly with governments and businesses to more speedily identify harmful or false content.

Activist Angela Davis says that these times feel “very different” from anything she’s experienced before—entire generations are across the globe banding together to fight for what is right, and there is massive potential for us to significantly change for the better.

If you’re feeling intimidated by their passion for truth and fairness, then perhaps a look in the mirror is warranted. We all have a part to play in making this world a kinder, safer, truer place for one another.