A warm welcome to the Deeper newsletter, dear reader!

You’re reading this because, just like us, you’re tired of the non-stop tech and startup news cycle, where there seems to be something new and trendy to keep up with in Southeast Asia.

What you want to know about is the important stuff that matters—period.

And that’s what we’re bringing to you. We’ll dive deep into a trending topic in Southeast Asian tech, and their impact on society (i.e. me and you).

Sound compelling? Subscribe now, and we’ll send it straight to your inbox:

Without further ado, let’s dive in.

Hi everyone!

Long time no see. Ebi here.

Today’s edition of Deeper is inspired by the many protests being held over the past few weeks in Indonesia against a proposed omnibus law, RUU Cipta Lapangan Kerja.

Historically, it has been difficult for foreign and local investors to start businesses and make significant investments into Indonesia’s economy. Many of the country’s financial opportunities require that investors have Indonesian citizenship and a Kartu Tanda Penduduk (KTP) identity card number. There’s plenty of red tape to navigate—hence why the omnibus law was created.

Unfortunately, though the bill does make it easier for investors and businesses to operate within Indonesia, it also erodes workers’ rights. Businesses are allowed to engage with service providers and freelancers indefinitely instead of offering a full-time position; contracts can be terminated as the company sees fit.

Another clause that has been criticized allows the maximum hours of work per week to be increased should a business wish to “fulfill production needs”. The bill, critics have said, puts employees and ordinary people at the mercy of powerful corporations who ultimately care most about profit—much more than they do about any single individual’s holistic wellbeing.

What are we sacrificing in our rush to achieve growth, profit, and scale?

TL;DR: In order to live fulfilling lives, we must always strive to find meaning and purpose in the work that we do.

- New opportunities in Southeast Asia’s online economy

- A new global, open market for talents, services, and goods

- Commoditizing oneself to survive in a rapidly changing world

- Is tech enabling exploitation, or simply revealing what’s long been broken?

- Finding meaning and purpose

We’ve seen it said time and again: business is changing. In their digital transformations, companies are becoming faster, more agile, and more flexible. New developments in technology have allowed businesses to become much more efficient and productive; organizations are becoming smarter.

But in their rush to develop the Next Big Thing, how many businesses have neglected their people?

We argue that, just as businesses are becoming more customer-centric, governments and organizations should also become more people-focused. Rather than aiming for constant growth or profit, those in power must step down and out of their castles, remember that they are just as human as everybody else, and do their part in making the world a kinder place. This involves creating and upholding fairer laws and workplace policies.

New opportunities in Southeast Asia’s online economy

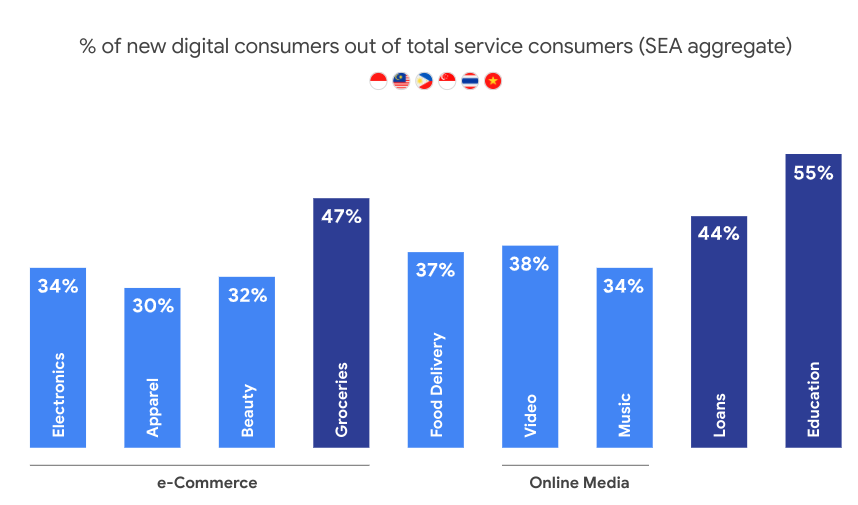

The latest Google e-conomy report revealed that 40 million in Southeast Asia have gotten connected since the beginning of this year—compared to just 10 million in 2019. That’s explosive growth.

As we move further into the future, it’s exciting to imagine what new digital developments might appear—and what sorts of work opportunities will arise for a motivated workforce, freelancer or otherwise.

The #smallbusiness hashtag on TikTok, for example, has gained 9.5 billion views; it’s full of independently-owned businesses dishing out business packaging tips, sharing suppliers and techniques, and pumping out how-to content in the hopes of landing onto users’ For You Page. Though a majority of these businesses sell do-it-yourself products or baked and cooked products such as cookies, DIY meals, and homemade jams and teas, some entrepreneurs have turned to businesses such as catfish-rearing and hydroponics.

With enough time and money, you can now start an online business in minutes simply by making an ecommerce account (such as Shopee or Tokopedia) and investing in products and packaging. And if you’re not business-inclined, you can make an Upwork, Fiverr, or LinkedIn profile (or all three) and get to work.

A new global, open market for talents, services, and goods

Although the Internet makes it easy for many to reach otherwise-untapped audiences and build profitable connections, it’s also frightening, especially for those in developed countries with higher costs of living. The fear of losing jobs to foreigners is one I often hear echoed among acquaintances living in Global North countries, and on job groups and forums.

Business competition is the highest in developing countries with weak labor protections and standards; there’s a reason so many fast-fashion and other massive-scale businesses choose to place their factories in Southeast Asian countries, where labor is far cheaper. So what happens when that phenomenon begins spreading to creative industries, too?

When a freelancer based in Southeast Asia can do the same work as you for a fraction of the fee, how can you convince businesses to choose you?

There are plenty of online platforms for people to find jobs. You’ve got OnlineJobs in the Philippines and Sribulancer in Indonesia, both of which promise thousands of potential job opportunities. Vlance in Vietnam boasts a talent pool of 500,000 freelancers. Then you’ve also got online Facebook groups and subreddits like r/hiring which are dedicated to sharing possible job opportunities and outsourced work.

Unfortunately, there is no real international set of guidelines on how work must be governed. The closest we have to an international agreement on workers’ rights is the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. The ILO is a UN agency, and the Declaration, which was adopted in 1998, requires member states to promote four general labor principles:

- freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining

- the elimination of forced or compulsory labor

- the abolition of child labor

- the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation

These principles don’t even begin to touch on the intricacies of the global labor market. For example—even though it can be lucrative for a content writer from Southeast Asia to work for international publications, they have little to no recourse if payment is not made. Do work contracts even apply if you’re not in the country?

Payments are another issue. International transfers are often hit with transfer and conversion fees, not to mention long and frustrating delays; there are cases of money being held indefinitely by digital banks and payment facilitators like PayPal to fight against fraud and potential money laundering. How do you pay and report taxes on remote or freelance earnings that cross borders?

Though online work and international online businesses are beginning to gain traction, there are still certain hurdles that must be addressed to truly develop a global economy. Clarity is needed to define what a worker looks like in this new era, and how they are to be protected when vying for survival. It is the responsibility of governments to balance workers’ rights and, indeed, protect their constituents, against the interests of private corporations.

Commoditizing oneself to survive in a rapidly changing world

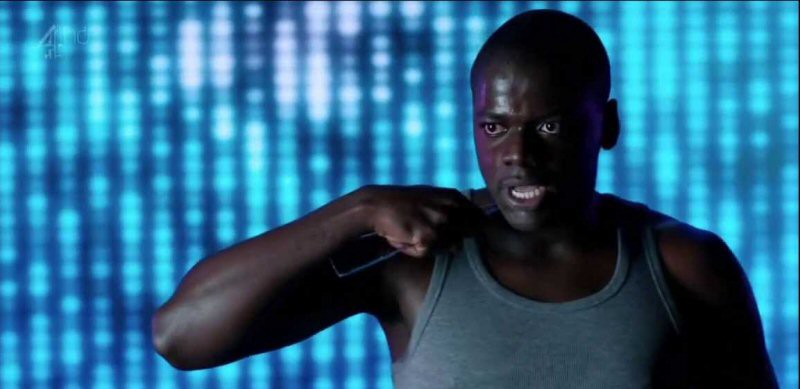

Though the Season 1 episode of Black Mirror, Fifteen Million Merits, isn’t without its flaws, it raises some great questions about the “self” in a global economy and modern world. We could argue that humans have always been valued based on how much they can create. We trade our time and efforts for wages, which are theoretically set fairly and proportionally to our worth (but which, more often than not, are arbitrary).

In the past, most of our opportunities for survival revolved around becoming an employee and working for someone else, or gathering the connections needed to become an entrepreneur. Nowadays, though, there are plenty of platforms out there for you to “sell yourself” instantly—from Twitch to Upwork to—yes, even Onlyfans.

The price you set for yourself might be based on your market research, your feelings of self-worth, and many other factors. OnlyFans, for example, allows you to set a minimum subscription of US$4.99 per month for your adult content; the maximum subscription price is US$49.99 per month. Creators can also set up tips or paid private messages starting at just US$5.

But that begs more questions: what paradigms should we use to value ourselves, and are we requesting fair remuneration for our services? Now that we have more information and transparency upon which we can set our fees, does that mean that we are finally receiving what we deserve? Does the price that people are willing to pay for our content and our time reflect our true worth?

Is tech enabling exploitation, or simply revealing what’s long been broken?

In the past, businesses were able to get away with labor exploitation because there was no solidarity and few protections in place for workers.

This is something heavily discussed in Upton Sinclair’s 1906 book The Jungle. Torrid descriptions of grueling, back-breaking factory work, day in and day out, fill hundreds and hundreds of pages—with workers always being replaced by someone a little bit hungrier, a little more desperate. These conditions are so utterly horrifying to the protagonist and life is so exhausting that he eventually becomes a socialist and joins a union to advocate for worker rights.

It’s interesting that a book written in 1906 is so highly relevant now. Many of us are still slaves to wages, and we are still highly replaceable. Not only that, we’ve even got added competition from robots and machine algorithms. We’re so used to feeling fear and anxiety about our survival that we’ve even programmed our robots to mimic that stress:

Can't believe they programed capitalism based anxieties into a robot https://t.co/RjWFU2By7P

— Nikko Nikko (@NikkoGuy) November 18, 2020

Some have argued that platforms like UpWork and OnlyFans are introducing harmful new ways for humans to exploit themselves—but what if they’re simply revealing what’s long been broken? What if they’re helping us to see that we’ve always been dehumanizing and devaluing ourselves? Some might argue that these platforms are actually allowing individuals to gain some of their power back.

Back to Black Mirror. Near the end of the episode, the main protagonist, Bing, appears live on an American Idol-esque talent show and rages against the system. He argues passionately that everyone is a soulless machine, doing the same thing day in and day out, and that there’s no truth in a world like that—no soul, no life, just empty and hateful complacency.

At the end of his monologue to the show’s judges, Bing pulls out a pointed shard of glass and threatens to kill himself live on television. But what happens next is astonishing—instead of kicking him off the show, the judges shower him with praise and offer him a twice-weekly, 30-minute TV show so he can educate the masses.

To our shock, Bing, who had originally been so upset about the exploitative nature of the system, gives in. He moves to a bigger cubicle with a window view of real trees and real birds (his previous cubicle was a tiny room of screens). Twice a week, he angrily criticizes the system to viewers, the same shard of glass pressed to his throat.

Still, no matter how much power Bing now has, he is still trapped in a glass box. It’s a strong analogy for our own world: no matter how much time we spend raising our position in the “game of life”, we, too, are trapped in boxes, unable to reach true freedom.

Finding meaning and purpose

Many people have developed their own answers to the question of “freedom”. Some work hard for the first few decades of their life and save and save and save so that they can enjoy financial freedom in their 40s or 50s. This is an approach partially supported by blogs like Singapore’s The Woke Salaryman.

In one interview, for example, TWS founders Ruiming and Wei Choon explained that the need for money is a fact of life. Though they would ideally like to spend all their time creating content and helping others gain financial freedom, they themselves are constrained by bills and limited resources. Hence, their approach is to try and balance their financial requirements with real authenticity, by truly listening to their readers and audience.

We cannot escape “the system” that binds us to the need for work. As workers, we can only make the most of it, like Homer does:

We urge business and political leaders to do more for the people they employ and protect, rather than focusing myopically on growth at all costs. In their book “Good Economics for Hard Times”, authors Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee highlight that countries should, instead, do more to improve their citizens’ welfare and our planet’s future.

It’s also been shown that wealth only increases happiness up to a certain point; there is no need for any single individual to control wealth that could last thousands of lifetimes.

Tech has the power to enable or destroy authentic human connection and value; it depends on how we use and interact with it. We’re beginning to see movements that use tech to support authentic connections. Singaporean organization Friendzone, for example, hosts online-offline group meets in efforts to help people build more meaningful relationships.

Though it’s natural to contact someone when we need help, we shouldn’t neglect warm, joyful friendships to the point that they become lonely, once-in-a-blue-moon check-ins.

It’s a tough world and it’s been a tough year, but we do have some choice in the kind of content we want to consume and the activities we want to pursue. In a time where tenderness and kindness are revolutionary, choose love. You don’t always have to upskill. You don’t always have to #hustle. It’s alright to slip in breaks once in a while and to tend to yourself, as best as you can.

Our love for the digital, shiny, and new should not blind us to the fact that there is a beautiful, warm world out there full of heartfelt connections with other living, breathing things. The grass is green, the air still beautiful, the rich colors of a sunset still so moving—and perhaps on those days, surrounded by those we hold dear to us, we can remember that these—not money, not fame—are what make life worth living.